Lonely Hearts Clubhouse:

pilot episode (episode 2!) 17 April, 2022

https://robmcminn.uk/2022/04/17/lonely-hearts-clubhouse-pilot-episode-episode-2/

Lonely Hearts Clubhouse:

pilot episode (episode 2!) 17 April, 2022

https://robmcminn.uk/2022/04/17/lonely-hearts-clubhouse-pilot-episode-episode-2/

Samuel Robinson, founder of Pansophers.com, discusses the 19th-century German Rosicrucian Alois Mailander and presents a guided meditation at the 'Rosicrucian Salon of the Arts' - hosted by SRIA London at the Atlantis Bookshop on the 16th October 2021.

https://bibliot3ca.com/descobrindo-o-segredo-de-m-o-adepto-por-tras-da-tradicao-ocidental/

Jimmy Page bought his house; the Beatles put him on the cover of Sgt. Pepper; Ozzy called him “Mr.” — but who exactly was Aleister Crowley, the “Great Beast 666”? TIDAL takes a deep dive into the legendary occultist’s strange, dark world.

by Shaun Brady

When Ozzy Osbourne posed the question “What went on in your head?” to one “Mr. Crowley,” on his 1980 solo debut Blizzard of Ozz, it was taken by many as absolute proof of the singer’s satanic tendencies. The late British occultist, poet and magician Aleister Crowley had been dubbed “the wickedest man in the world” and “a man we’d like to hang” by the British press during the first half of the 20th century. Even before his infamous bat-biting and Alamo urination incidents, the ex-Black Sabbath frontman seemed well on his way to inheriting both mantles.

But Osbourne’s song, co-written with guitarist Randy Rhoads and bassist Bob Daisley, sprang from honest curiosity rather than some infernal discipleship. “I never did this black-magic stuff,” Ozzy told Rolling Stone in 2002, insisting that he and his Sabbath bandmates “couldn’t conjure up a fart. … The reason I did ‘Mr. Crowley’ … was that everybody was talking about Aleister Crowley.”

Born in 1875, Crowley was raised in a fundamentalist Christian family and essentially spent his entire life repudiating their strict teachings. He was a polymath with a voracious appetite and an all-eclipsing ego who refused to be satisfied with anything short of godhood. He rose through the ranks and alienated himself from esoteric secret societies like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Ordo Templi Orientis, ultimately founding a religion known as Thelema and appointing himself its prophet.

Crowley’s study of “magick” — he added the k to differentiate his occult workings from simple illusion — led him on a path of experimentation that encompassed journeys to India and North Africa, sexual hedonism, drug abuse, sadomasochism and mysticism guided by his doctrine: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.”

That anything-goes dictum goes a long way towards explaining why Crowley — or at least his image — continues to enthrall musicians more than three-quarters of a century after his death in 1947. While Blizzard of Ozz served as many a young metalhead’s introduction to the name of Aleister Crowley (this writer included), it was far from the first time that the self-professed “Great Beast 666” had cast his spell on the rock world.

His bald visage appears in the upper-left-hand corner of the cover art for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, sandwiched between Indian guru Sri Yukteswar Giri and actress Mae West — appropriately enough, linking a spiritual leader and a sex symbol. Most famously, Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page spent a small fortune hoarding Crowleyana, including purchasing Boleskine, the magician’s dilapidated former home on Loch Ness.

Thelema was predicated on an approaching era in which the Egyptian deity Thmaist takes over from current ruler Horus, whose tenure Crowley referred to as the “reign of the crowned and conquering child” — an apt description of the lineage of rock idols anointed at an early age and frozen into perpetual adolescence. One of Crowley’s recent biographers, Gary Lachman, characterizes the Great Beast as “a colossal example of arrested development.” He cites the influence of Crowley’s self-centered philosophy on songs from Iggy Pop’s “I Need More” to the Doors’ “When the Music’s Over” and its declaration “We want the world and we want it now.”

Lachman, though a severe critic of Crowley’s more self-serving indulgences, is himself an example of his subject’s allure for the rock crowd. Prior to becoming an author and an expert on the occult, Lachman was known as Rock & Roll Hall of Famer Gary Valentine, the bassist for Blondie early in the band’s career. Although it was recorded after he left the band, he wrote the song “(I’m Always Touched by Your) Presence, Dear” under the sway of Crowley and other occultists. Its lyrics touch on theosophy, contacting “outer entities,” and the telepathic connection Lachman shared with his then-girlfriend.

It only took a generation after his passing for Crowley to transform from dangerous blasphemer to spiritual icon. His rebellion against established norms, advocacy for sexual freedom and spiritual questing all resonated with a counterculture shaking off the strictures of its elders. LSD guru Timothy Leary once claimed to be “carrying on much of the work that [Crowley] started,” as were “the ’60s themselves.” The opening lines to the Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows” (“Turn off your mind / Relax and float downstream”) are borrowed from one of Leary’s books, but the astral-traveling sentiment could be traced back to Crowley.

Not to be outdone, the Rolling Stones also delved into occult studies. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were mentored by the filmmaker and dedicated Thelemite Kenneth Anger, as reflected in “Sympathy for the Devil.” Jagger turned down the Lucifer role in Anger’s Lucifer Rising, but had scored and appeared in his Invocation of My Demon Brother. The cast list for Lucifer Rising ultimately included Jagger’s then-partner, singer Marianne Faithfull. Jimmy Page composed a score for the film that was ultimately rejected after a falling out with Anger (a habit the director shared with Crowley). The filmmaker ultimately turned to the Manson Family’s Bobby Beausoleil (a member of Arthur Lee’s band the Grass Roots, who became Love) to compose the soundtrack from his prison cell.

Page turned his attention to restoring Boleskine, commissioning artist Charles Pace to recreate the murals from Crowley’s Abbey of Thelema in Sicily (which had been restored by Anger, decades after Crowley’s eviction by Benito Mussolini). The grounds show up in the concert film The Song Remains the Same, and the album art for Led Zeppelin IV was illustrated with mystical symbols. Excluding the dubious accusations of backmasking that have long dogged “Stairway to Heaven,” the band’s lyrics borrow far more from Tolkien and American blues than from Crowley or his pagan peers.

Keyboardist and singer Graham Bond, whose band the Graham Bond Organisation was a launching pad for the likes of jazz-rock guitar hero John McLaughlin and Cream’s Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, took his Crowley obsession to more tragic lengths. Albums like 1970’s Holy Magick and ’71’s We Put Our Magick on You are laced with references to Thelema and other esoterica, but Bond sank into mental illness, claiming to be Crowley’s son before throwing himself in front of a train in 1974.

David Bowie was dabbling in any number of fringe interests — Egyptian mysticism, the Kabbalah, the Nazi hunt for the Holy Grail — by the time he recorded Hunky Dory in 1971, and the Beast hardly escaped his notice. The lyrics for “Quicksand” begin, “I’m closer to the Golden Dawn / Immersed in Crowley’s uniform / Of imagery.” Even Sly and the Family Stone summoned Crowley, however inadvertently: “Everybody Is a Star” echoes Crowley’s “Every man and every woman is a star,” one of the opening lines of his The Book of the Law. The sentiment was in the air.

No genre has taken to Crowley quite like heavy metal, even if, as with Ozzy’s Gold-selling single, the understanding of the man and his gospel often seems tenuous at best. Though they took their name from an Italian horror movie, Black Sabbath also drew inspiration from a 1934 novel, Dennis Wheatley’s The Devil Rides Out, whose main villain was based on Crowley. A 1968 film adaptation laid the groundwork for a host of “high-society cult” narratives, from Val Lewton’s sardonic The Seventh Victim to Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby.

Iron Maiden, perhaps the most literarily inclined of metal bands, has evoked Crowley often. The title song from The Number of the Beast turns Crowley’s adopted numerals into a singalong, while the later “Moonchild” is based on Crowley’s 1917 novel of the same name. Lead singer Bruce Dickinson even penned a tongue-in-cheek 2008 horror film, called alternately Chemical Wedding or Crowley, in which the occultist is reincarnated through a modern-day Cambridge professor.

The title of Celtic Frost’s 1985 classic To Mega Therion is another of Crowley’s many pseudonyms — it’s Greek for “The Great Beast” — though it wasn’t until 20 years later that they directly cited his work, in the song “Os Abysmi Vel Daath.” Marilyn Manson’s “Misery Machine” charts a joyride “down Highway 666 … to the Abbey of Thelema.”

More experimental and industrial bands returned the embrace of Crowley to his actual philosophies rather than to his cartoonish depiction. Current 93 were virtual Crowley apostles, with founder David Tibet castigating the metal contingent for their misinterpretations in a 1983 article. Throbbing Gristle’s “United” features a chant of “Love is the law,” half of Crowley’s traditional sign-off, “Love is the law, love under will.” Killing Joke’s “The Fall of Because” took its title from Crowley’s writings, and Secret Chiefs 3, led by Mr. Bungle/Faith No More guitarist Trey Spruance, was named for the mysterious figures guiding humanity in belief systems including Thelema and the Golden Dawn.

You expect to find Crowley lurking in the shadows conjured by metal and industrial bands — genres traditionally drawn to the darkness. But his influence is widespread enough that even blue-eyed soul singer Daryl Hall evokes him on his 1980 solo album, Sacred Songs. “Without Tears,” the album’s closing track, is based on the posthumously published book Magick Without Tears.

In recent years, Crowley T-shirts have been spotted on both provocateurs (Tyler, the Creator) and non-diabolical pop stars (Kevin Jonas). A decade ago, Ciara could be seen in a matching shawl and boots that touted the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. JAY-Z donned a hoodie emblazoned with “Do What Thou Wilt” in a behind-the-scenes clip of his post-apocalyptic video for “Run This Town” — itself accused, however unconvincingly, of smuggling occult imagery into the mainstream. The rapper Ab-Soul immersed himself in Crowley research for his 2016 LP Do What Thou Wilt.

Which might provide some glimmer of an answer to Ozzy’s conundrum. What really went on in Crowley’s head was the allure of the forbidden and transgressive, which isn’t as esoteric or unusual as we might want to believe.

Occultist, poet, chess player, mountain climber, sexual deviant…..all these things Crowley has been called, yet his influence on occultism is still felt today. He stands 12 inches tall atop a round base engraved with a unicursal hexagram, emblem adopted for magical use by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn over 100 years ago. He is garbed in his atypical three piece suit, holding a pipe like the English Gentleman he was. will note the expression is reminiscent of the legendary “Great Beast 666” portrait the most recognizable image of Crowley himself.

Did Jack Parsons Blow Himself Up? 30/09/2021

(https://youtu.be/x8DU-nMfFGg)

The life and death of Jack Parsons is stranger than fiction. An intense commitment to Black magic and the occult, a shared lover with L. Ron Hubbard, and a founding father of rocket science—Jack’s curiosity and mischief-making propelled him to success and eventually drove him to his death. But it’s the details of his death that still remain unknown...was it an accident... suicide, murder or the work of Satan? In this episode, we reexamine the last days of this rocket man and attempt to solve the mystery of what really sent him to the moon.

Directed & Edited by Derrick Deblasis , Written & Hosted by Tom Carroll ,Produced by Derrick Deblasis & Tom Carroll,Cinematography by Henry Loevner, Derrick Deblasis, Steven Kanter & Tom Carroll,Original Music by Jeffery Brodsky,Theme Song by Yuri Beats,Production Assistant: Chance Grey,Starring, Derrick Deblasis as Jack Parsons Claudia Restrepo as Majorie Cameron Colin Weatherby as L. Ron Hubbard Tim De La Motte as Aleister Crowley ,Special Thanks, Peter Lunenfeld Catherine Auman

https://www.mandragoramagika.com/other-countries

ARE YOU A SEEKER LOOKING FOR A COVEN, GROUP, MEET UP? WITCHES AND PAGANS DO NOT PROSELYTIZE SO IT'S UP TO THE SEEKER TO SEARCH, CONTACT AND FIND TEACHERS. THIS IS JUST A RESOURCE FOR YOU TO REACH OUT.

We are happy to present this page for covens, groups and organizations in the locations listed below. This information on these pages is presented as submitted, we do not know many of the groups that are represented here and only remove groups if serious verifiable allegations are brought to our attention. We encourage you to please use your discretion when meeting strangers, and due diligence in researching the tradition and reputation of the leaders. We suggest you read this BLOG post prior to meeting possible teachers, as well as the DISCLAIMER page.

Confraria Solaris Umbra is a contemporary brotherhood, founded in Portugal in 2004 by several initiates in the Art, from different traditions of Witchcraft, its purpose is based on the instruction of every individual who truly wants to practice the Art of Witchcraft in Portuguese territory; drawing from this millenary Art, among its plural purposes, the improvement of the individual, personal fulfillment and (re)union with the personal Daemon, the initiatory tutor and guardian spirit of every man and woman.

This class of spirits is known throughout history by various names in various religious and spiritual traditions; the best known being through the Roman Apostolic Church as the Guardian Angel, or in spiritualism as the Guiding Spirit, or in other occult traditions as the Personal Guardian; in the brotherhood we use the nomenclature Daemon, as this term comes from ancient Greece, a concept that has nothing to do with the late concept of Demon, we open this parenthesis to clarify this difference that causes so much confusion to those who do not know this meaning.

The instruction of Solaris Umbra's knowledge is structured in 3 degrees or hierarchical stages of knowledge and practices taught by the all Craftsmen Instructors (Opifex) who makes up the brotherhood.

________________________________________________________________

CITY: Tomar

TRADITION OR SPIRITUAL PATH: Alexandrian Witchcraft Tradition

CONTACT NAME: Karagan Griffith

EMAIL: covendetomar@gmail.com

WEBSITE: www.covendetomar.com

UPDATED: 11/17/2021

O coven de Tomar, é o Coven da Tradição Alexandrina da Wicca (bruxaria moderna), na Linha de Queensberry na cidade de Tomar. O coven reúne-se todos os Sabbats e Esbats, bem como em círculos de treino e de trabalho mágico. No trabalho interno de Coven, os membros desenvolvem as suas capacidades na experiência ritualística tradicional, observando os mistérios internos da bruxaria moderna no contexto da prática tradicional Alexandrina. O Coven de Tomar está neste momento a considerar pedidos sinceros para iniciação e treino tradicional na Tradição Alexandrina da Wicca em Portugal para o final de 2021, inicio de 2022.

________________________________________________________________

TRADITION OR SPIRITUAL PATH: Wicca/Chi

CONTACT NAME: Moema

EMAIL: lolaliepop@gmail.com

We are mostly wiccan but the structure to our power revolves around chi and the basic elements. We have a history of germanic and Celtic people laced in our blood. We celebrate all holidays but as we have younger members in our coven we go all out on Litha and Beltane Looking to make connections.

ASTOUNDING SECRETS OF THE DEVIL

WORSHIPPERS’ MYSTIC LOVE CULT

by William

climbing.com

Aleister Crowley (October 12, 1875 – December 1,

1947), English mountaineer, more commonly known as an occultist

and the founder of the Thelema religious movement. novelist, playwright, poet, and painter.

While his climbing accomplishments are lesser-known, Crowley is

notable as the first Westerner to attempt K2 (8,611 meters), in 1902,

with Oscar Eckenstein, and for leading an attempt on Kanchenjunga (8,586

meters). The latter expedition, although also unsuccessful, purportedly

reached the highest point that any human being had achieved on any

mountain at the time (7,620 meters/25,000 feet). Both peaks were not

summited until over 50 years after Crowley’s attempts.

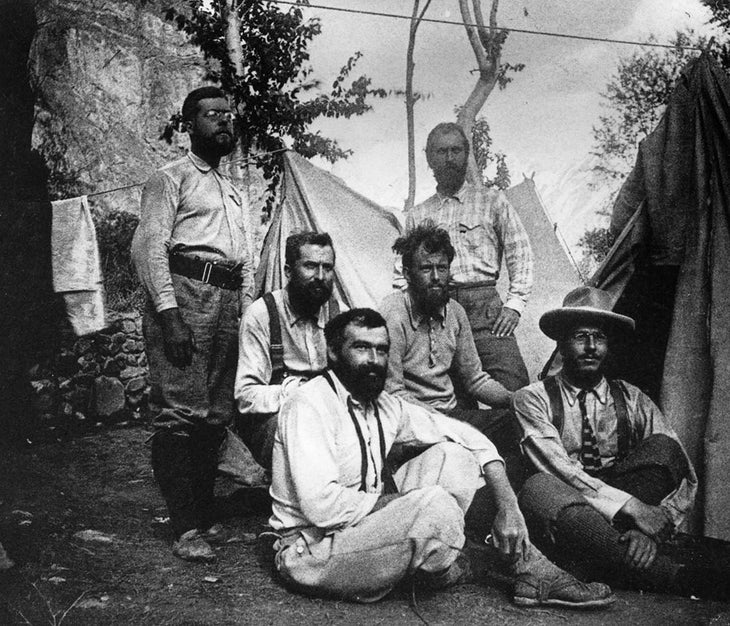

1902: English author, occultist, magician

and mountaineer Aleister Crowley (1875 – 1947)

(second from left) with

companions during an expedition. (Photo: Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Crowley’s accomplishments as an alpinist

were significant for the time. In addition to his unsuccessful

expeditions on K2 and Kanchenjunga, he successfully climbed several

peaks in the Alps and put up a string of hard first ascents on rock in

the Lake District and Beachy Head, as well as other sites in the United

Kingdom, during the 1890s.

https://www.climbing.com/people/aleister-crowley-the-wickedest-climber-ever